Surveys are a tricky data collection method. On the one hand, they enable reaching thousands of people and gathering a magnitude of data in a short timeframe. On the other hand, they rarely capture the information they ought to. The reason for that is often bad design.

Survey design is no joke. A fool can ask more questions than seven wise men can answer but only a few can ask GOOD questions. Asking the right questions, however, is essential for a questionnaire to work.

This became apparent yet again when the other day I was sent a survey to fill in. With permission from the author, I would like to go through this survey to demonstrate what exactly is wrong with it and why it will fail at extracting the information the researchers were going after. (You can find the full survey at the end of this article.)

Survey vs interview

An interview is a great tool for exploring the domain of interest. How to conduct good interviews is a whole other topic which we will not cover here, but an interview enables the researcher to probe deeper, change questions on the go, and get a general understanding of the problem. From the answers, a hypothesis can be formed.

Surveys work better as a confirmatory tool. They enable gathering (mostly) quantitative data supporting or contradicting the already formulated hypothesis. Surveys are not great for forming initial understandings because asking follow-up questions and clarifications is either impossible or at the very least resource-intensive and bothersome.

Therefore, interviews are useful for gathering qualitative data and understanding the problem domain while surveys allow getting feedback on an existing hypothesis.

Avoid Domain jargon

This question uses specialised terminology from the domain of User Research. “Use case” is an example of domain-specific jargon and it stands for a specific situation in which a product or a service could be used. Not everyone will be able to fully comprehend what the term “use case” means. This forces the respondent to draw conclusions from incomplete information which can result in misunderstanding and invalid answers.

The proposed answers and the context of the questionnaire imply that the researcher wants to know why the participant engages in conference calls, not what the conference calls are generally used for. However, a question that would have avoided this vagueness and confused the participants less would have been either “What do you use conference calls for?” or “Why do you attend conference calls?”.

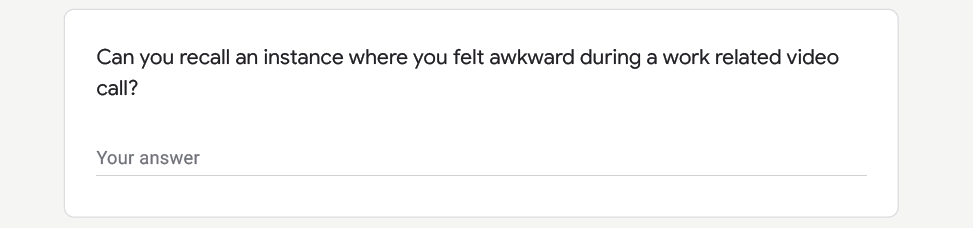

Expect yes/no answers to Yes/no questions

All of the answers above are valid answers to the questions asked, but give absolutely no useful information to the researcher. Yes/no questions will elicit yes/no answers. Hopefully, not everyone takes questions that literally but there are some annoying people out there (like me).

I think it is safe to say that the author of this survey did not expect such answers but instead was looking for an elaboration. Instead of asking “Are…” or “Can…” these questions could be formulated in a way that enables answering with an example, description, or “Not applicable to me.”

For example, the question “Recall an instance where you felt awkward during a work-related video call. What happened?” can be answered with “Haven’t felt awkward” or “Yeah, I forgot I wasn’t wearing pants and stood up to get something from a shelf and everyone saw a close-up of my diddly-doo”.

Other more probing formulations of the questions in that picture:

“Which parts of remote meetings feel unnatural to you?”

“Why did you experience disengagement (at your last remote meeting)?”

Of course, open-ended questions like the ones above are somewhat bothersome for respondents to answer as writing down an elaborate answer takes time and effort. I am often guilty of closing surveys mid-way when I see that there are too many open-ended questions, especially if I am filling in the survey on mobile. If I am not getting paid to answer, why should I spend my valuable time and energy on this?

Open-ended questions imply that the researcher has not done any preliminary work to narrow down the problem space and expects the poor respondents to do that work for her. This is exactly where conducting qualitative interviews before creating the survey comes in handy. Based on the interviews, a hypothesis can be formulated. The hypothesis can then be rejected or “confirmed” with the survey.

Here are some more bad examples of yes/no questions. As a little exercise, try to rephrase them so that they elicit the information you need.

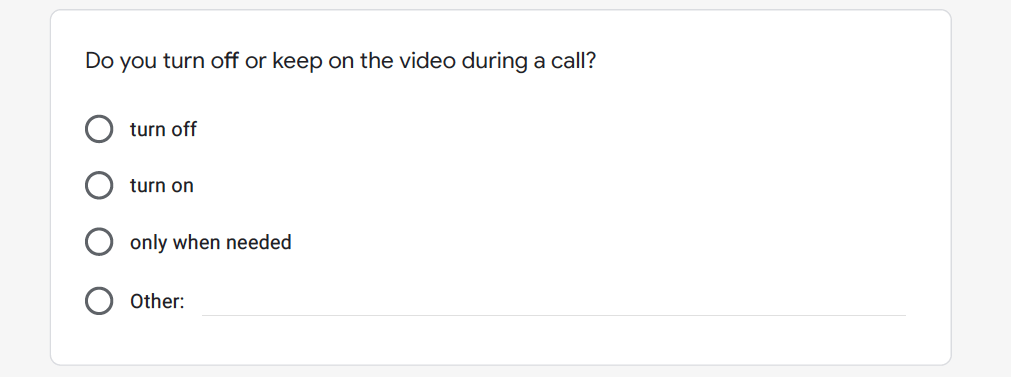

Offer a selection of answers

These questions are actually quite nice. They offer some pre-set answers that were established from preliminary work, e.g. interviews or desk research. They also feature the option “other” for respondents to add the answers that were not included by the author of the survey.

Providing the respondent with a selection reduces their cognitive workload and makes the whole survey experience more pleasant. Suddenly, the respondent does not have to dig deep in their brain to recall all the answers, but can simply tick the ones that fit.

The option for adding custom answers is a fallback in case the researcher forgot to include a potential answer or was not aware of alternatives. The worst case is when a question is mandatory, none of the answers suit, yet there is no option to add a custom one. Allowing custom answers can rarely do any bad.

Be as specific as possible

The option “only when needed” can be understood in two different ways. Either “turn off the video only when needed” or “turn on the video only when needed”. These are obviously very different from each other and right now that survey does not capture what the respondent actually means. They should be split into two separate options.

This question needs elaboration. What is meant by disengagement? Did I as a participant feel disengaged? Did I notice that my teammates were not paying attention to me? Was the manager not listening to one of my teammates? Each respondent might read this question differently and, as such, the data from this question will tell the researcher absolutely nothing and should be discarded when drawing conclusions.

Load a moving van, not a question

Bias is easy to cause and difficult to recognise. “Did you like the food?” is more likely to elicit positive answers than “What did you think of the food?” In research, we want brutal honesty to ensure the best possible results and the success of the whole project.

The question in this example is a loaded question, meaning it already implies that the respondent has felt awkward. In reality, we do not know that. It might be that they are the most comfortable person on Earth who never feels awkward. A question that claims they should have felt awkward at some point can make them doubt themselves. Of course, the question in this specific example is softened by the beginning “Can you recall…” but that poses a whole other problem as we saw before.

Additionally, this question implies that preliminary research revealed that most people feel awkward during video calls. By looking at the rest of the survey, I do not think a lot of preliminary research was conducted, however.

If the researcher simply wanted to capture how people feel during work-related video calls, this question is no good. A better one would be, “How do you usually feel during work-related video calls?” or “How did you feel during your most recent work-related video call?”.

Don’t repeat yourself like a broken record

“Why?”, “why?”, “why?”… That’s what a 5-year-old asks when trying to understand how the world works. Do not get me wrong, curiosity is amazing and we should not lose if after elementary school, but in this survey question “why” becomes redundant. Adding a subtitle is unnecessary. Simply put “Why do you use that tool?”.

Here one could even propose answers to select from if some trends for using certain tools emerged from preliminary interviews, e.g. “used by my company”, “has the required functionality”, “good looks”, “easy to use”.

Long story short…

Creating a proper survey is a difficult task. Badly made surveys are tedious to fill in and can yield inaccurate results. Forming premises based on data gathered from an improperly designed survey can even become detrimental to the success of the whole project.

Do interviews instead.

On a side note, if anyone ever needs feedback on their survey or someone to do a pilot run with, let me know. I enjoy ripping surveys to shreds.